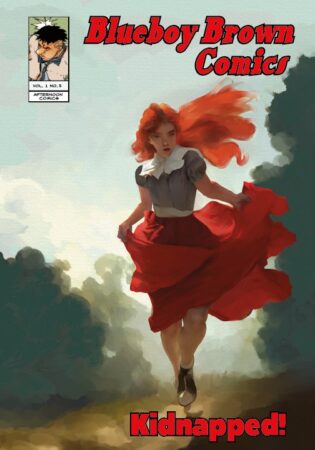

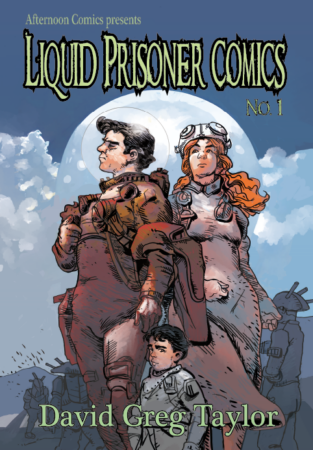

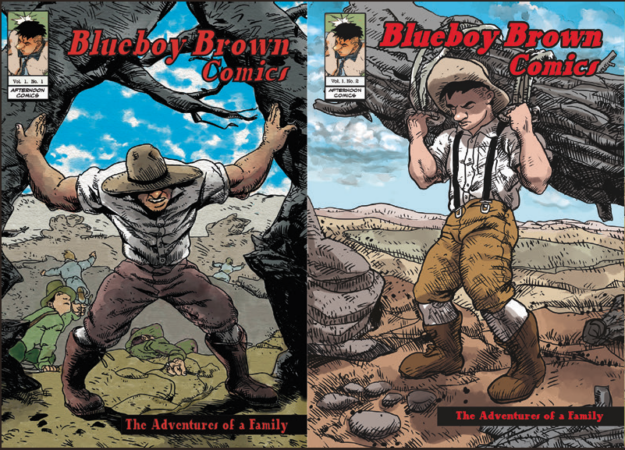

Afternoon Comics is owned by David Greg Taylor and currently features Blueboy Brown and Liquid Prisoner.

Inspired by sources not common in comics, and illustrated with the same fine draftsmen quality style of art found in comics past and other illustrated art fields, Davids comics give an edge of new excitement lost in today’s industry. Let’s find out more!

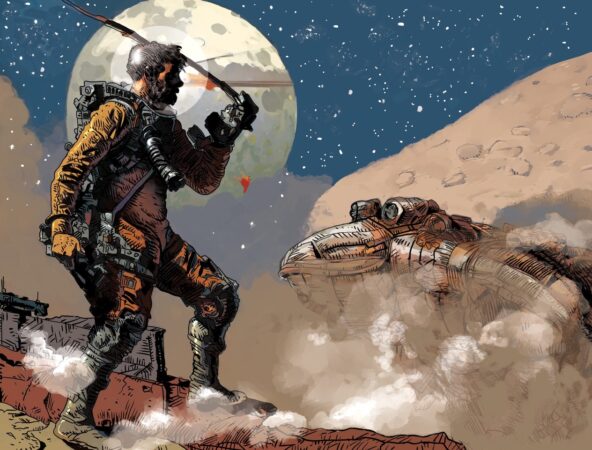

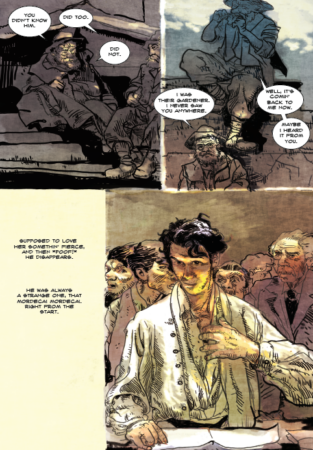

Joeseph Simon: Under the Afternoon Comics banner, you have two ongoing series. Blueboy Brown and Liquid Prisoner, which just debuted. Blueboy Brown is an extended story of a specific family through different generations. It’s also a lot more! Liquid Prisoner is a kind of surrealist science fiction. Both series are written and illustrated by you. There is a Blueboy Brown feel at the start of Liquid Prisoner. That quickly fades away as the story transforms into something mysterious not only to the reader, but to our hero and his family.

What would you like people to know about Liquid Prisoner?

David Greg Taylor: I guess I’m a part of the zeitgeist, thinking about the rise of the machine. The Liquid Prisoner is a different machine, however. I have not seen my take on it done. I haven’t read everything (on purpose), but this one has a set of problems I don’t believe you’ll find in another story.

Joeseph Simon: What about Blueboy Brown?

Joeseph Simon: What about Blueboy Brown?

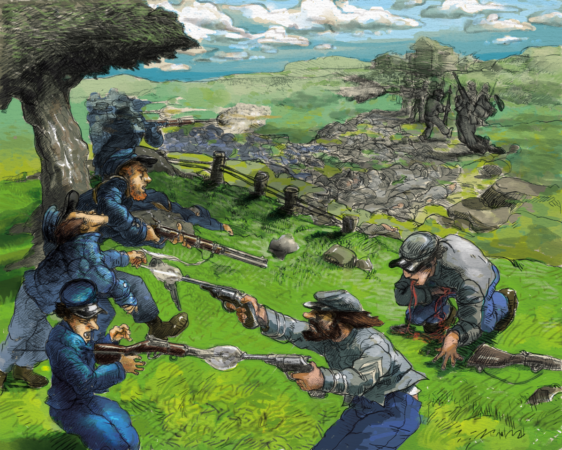

David Greg Taylor: Blueboy is my grandfather’s brother. He was a near-giant, six-foot eight, and he was a lumberjack. This series is a love story to my extended family. I still know his descendants and most of my cousins. It’s a big bunch. However, they never went through what poor Blueboy Brown is about to experience. They just had to endure the Great Depression and World War II!

Joeseph Simon: Your art is very idiocentric to your own visual identity and the writing recalls literature more than comics. You can see this in both series. More so, there is a studied self-awareness to your creativity where, correct me if I’m wrong, everything is well thought out and planned. Where the story doesn’t seem minimalistic, it is in the sense that there is a reason for everything.

David Greg Taylor: I was mentored, to some extent, by Rolf Fjelde, the Ibsen scholar. I met him at Pratt when I took his course on Ibsen and one on Shakespeare, Euripides, Moliere, etc. He really set me on a new path. We became friends and he invited me to Ibsen Society meetings and performances of his translations of Ibsen (they are the best. His grandfather and Ibsen were friends). I’m very taken by Ibsen’s development of his last twelve prose plays, and Shakespeare. Liquid Prisoner is an homage to the Bard since it is a line in a sonnet of his.

Sonnet V

Those hours, that with gentle work did frame

The lovely gaze where every eye doth dwell,

Will play the tyrants to the very same

And that unfair which fairly doth excel;

For never-resting time leads summer on

To hideous winter, and confounds him there;

Sap checked with frost, and lusty leaves quite gone,

Beauty o’er-snowed and bareness every where:

Then were not summer’s distillation left,

A liquid prisoner pent in walls of glass,

Beauty’s effect with beauty were bereft,

Nor it, nor no remembrance what it was:

But flowers distilled, though they with winter meet,

Leese but their show; their substance still lives sweet.

I thought it was a wonderful name for a character and the comic follows. The sonnets V and VI are about how bittersweet life is.

I thought it was a wonderful name for a character and the comic follows. The sonnets V and VI are about how bittersweet life is.

Now, to speak of the storyline development, that’s something very purposeful and points to the influence Ibsen has had on me, even if I’m not doing Ibsenian storylines. I wrote when I was young, and even got a small thing mentioned about me in The Comics Journal back in 1985, but I was a horrid writer. I held off until I decided I might have the chops to pull it off. This was after writing stories for a Native American journal, Whisper ‘n Thunder over a decade ago. I did a series of short stories I named Driving Down Pass Road. If I live long enough, I’ll turn that into comics. It too is a sort of love story to my Comanche and Seminole cousins. I have had some cool cousins.

Joeseph Simon: Very interesting names! For those who don’t know these two men:

Rolf G. Fjelde (passed September 2002) was an American playwright, educator, and poet. He also was the founding president of the Ibsen Society of America which is dedicated to promoting academic and public interest in the work of Henrik Ibsen.

Henrik Johan Ibsen (passed May 1906) ) was a Norwegian playwright and theatre director. As one of the founders of modernism in theatre, Ibsen is often referred to as “the father of realism” and one of the most influential playwrights of his time.

To your knowledge, are your comics the first comics to be influenced by Ibsen?

David Greg Taylor: I can’t say for sure if I know that. It’s been 37 years since I took Rolf Fjelde’s Ibsen class. The influence that is in me from Ibsen is the !WHAM! I got from his last play, When We Dead Awaken. I went with Rolf to a performance of his translation of the play during my second year of grad school. It’s a great play and the capstone of his oeuvre. In my college teaching career, I’ve spent years teaching plot structure in Humanities and cinema history classes. This has had a major effect on my writing. Then add the French cinema theorist Andre Bazin to the mix. Both Ibsen and Bazin were proponents of realism. I too am an aficionado of realism with a caveat of what is reality?

Joeseph Simon: I really enjoyed Liquid Prisoner. One of the high points for me is the sense of wonder and the question “What’s going to happen next?

David Greg Taylor: Thank you! Life is bittersweet, and full of suffering, but there is something that transcends that. Such a thing takes time to develop.

Joeseph Simon: Any reveals you can mention?

David Greg Taylor: Despite any intelligence we may possess, there are gaps that only life can teach us, and then only if we are very lucky. I’m 70 yrs. old now, in pretty good shape, and have more stories than I probably have time for. No one lives forever. I’m very lucky, for I have rubbed elbows with some very deep thinkers who had a great effect on me. I’m synthesizing these influences in the stories I’ll do before I shove off for the next great adventure. I’m keeping my cards close to my vest, other than looking for something out of left field.

Joeseph Simon: You might consider yourself old-timers, but what you are doing with these comics is bridging, not just fine illustration with comics, not just theater, literature, and other influences with comics, you’re introducing comics to those fields in new and exciting ways.

I think the comic book industry often cannibalizes itself, regurgitating the past with whatever passes for modern takes or twists.

It’s people who bring in new perspectives and ideas that make the industry, readers, and people who want to expand the industry.

Given all that, in your opinion, what is the industry really missing about comics that could make things better?

David Greg Taylor: Well, first the thing that drives me is not what drives the big publishers. From my teaching experience I have become very well acquainted with auteurs like Orson Wells, Roberto Rossellini, Kurosawa, Goddard. I’m driven by storytelling and more than that, by meditating on the end result of stories. Where the character(s) end up and how they get there. I think that demands life experience, and you can’t just churn out issues. For me, that takes time, and forgetting about the market. A corporation can’t do that (DC and Marvel are just branches of large, multinational corporations). I’m kind of over vampires, zombies, crime fighters wearing ski suits and breaking the laws of nature (the Flash can’t run faster than the speed of light because his mass would become infinite as he approached it…yeah, I know it’s fantasy and I love the Flash since I was ten years old and Carmine Infantino did it).

I think you’re correct about comics churning out recycled stories. It’s difficult to come up with original stories and characters. Many years ago I came upon Mortimer Adler speaking about learning and how in reading one should always choose something that is just beyond one’s intellectual reach. I tackled Aristotle and Aquinas that way, and by the time I read Edith Stein, I could handle her (even though she’s smarter than anyone that’s lived in the last century. Certainly far more intelligent than me).

Then, when the light goes on and you get a story, it’s more likely to be a synthesis of your life and reading experience. You might b reak the mold.

Joeseph Simon: Everyone should encourage learning from the generations before them. You can never know what a person has gone through and experienced until your told. Even in with today’s technology, a lot of knowledge, not to mention skill and ability is communicated in person as opposed to via the internet.

Joeseph Simon: Everyone should encourage learning from the generations before them. You can never know what a person has gone through and experienced until your told. Even in with today’s technology, a lot of knowledge, not to mention skill and ability is communicated in person as opposed to via the internet.

The problem is it takes getting old to realize and, as a result, younger people are likely to might miss out on those opportunities.

For those listening, what advice would you give people today? People in general, as well as creators, readers, and industry leaders of the comic industry?

David Greg Taylor: There is a lot of ancient knowledge people are ignoring these days. It’s part of the modern urge to erase the past and replace it with something new and shiny. Ibsen didn’t create his last twelve prose plays that Rolf Fjelde translated from whole cloth. The maxim of When We Dead Awaken is straight out of Socrates: “The unexamined life is not worth living.” Ibsen did it in a masterful way, but it is telling that he lived many years of difficulties and suffering to reach that place. His character Rubek in the opening scene is at a spa in the mountains, and his companion Maja remarks on the quiet of the place and they begin an examination of their lives together. It starts an unraveling of the postures they have assumed to get through daily life.

Now, there is no superhero moving mountains here, and the action is in the dialogue and the climactic scene leaves you aghast, but along the way, if you apply the lessons of the play to yourself, you understand Ibsen is pointing a laser at the way people live their lives. That’s what great art does. It’s really the reason I returned to comics, since it is theater in another form. I do feel an affinity to Ibsen and the wealth I derived from studying with Professor Fjelde. I’m doing it my way, but if the end result is an examined life, then I have made my contribution to a tradition that stretches back for millennia. What greater goal could I have as an artist?

My delight is in being writer, set designer, actor and director of this form of theater.

Joeseph Simon: How do you think you can bring people in from the different fields that you are part of….fine art world, Theatre, avant-garde, and so on, and get them into comics or get comic  people into those fields of art?

people into those fields of art?

What comic’s would you turn them onto?

David Greg Taylor: That’s a tough question. First, comics in the United States has been geared towards 12-year olds since the early days of comics. The first comic I read that didn’t do that was Jean Giraud’s Lt. Blueberry. If you’re in the States, as an artist you’d have get past the attitude we have here towards comics as not worthy of good literature.

I like Torpedo a great deal. (Alex Toth started that series, ‘natch.)

In the end, think of synthesizing your experiences as an artist, but don’t by limited by what other people do. I’d tell visual artists to learn to write. That’s not an easy task. Writing fiction is like writing music or poetry in that there is an ebb and flow to the storyline, like music that builds to its crescendo or a play that builds to the climax and then the denouement. Muscled characters smashing each other every page doesn’t cut it for me. I guess I really do like realism, but with a twist. Unlikely things happen to my characters, but they only fly in their dreams. I know from experience flying dreams are a symbol of the desire to be free. But there is no freedom like we imagine birds have it. When we think like that, we forgot the eagles and hawks of the bird kingdom. We are sparrows.

Joeseph Simon: While very different than Jack Katz’s amazing First Kingdom, after reading Liquid Prisoner, I found myself in that same vibe when I read First Kingdom. First Kingdom was uniquely Jack Katz. It was a passion, one where it felt like the creator was compelled to make it a reality.

David Greg Taylor: I’ll take that as a great compliment!

Joeseph Simon: Instead of being hired on to take over from another creator for a long-running comic series, what you are doing with both series is adding something new and of value to the comic industry.

I’m curious to your thoughts on what I just stated.

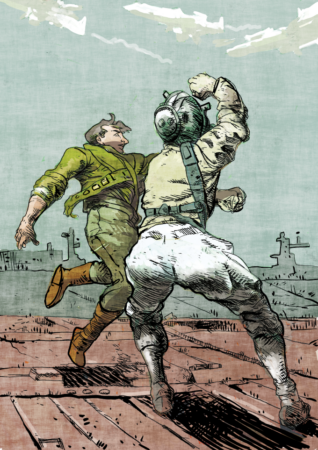

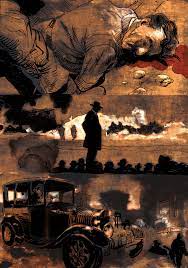

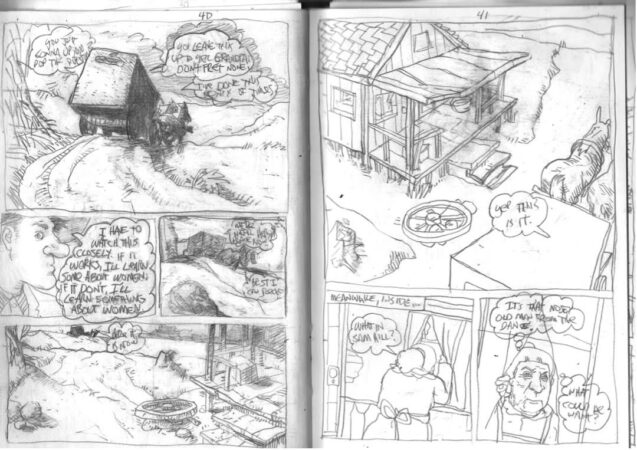

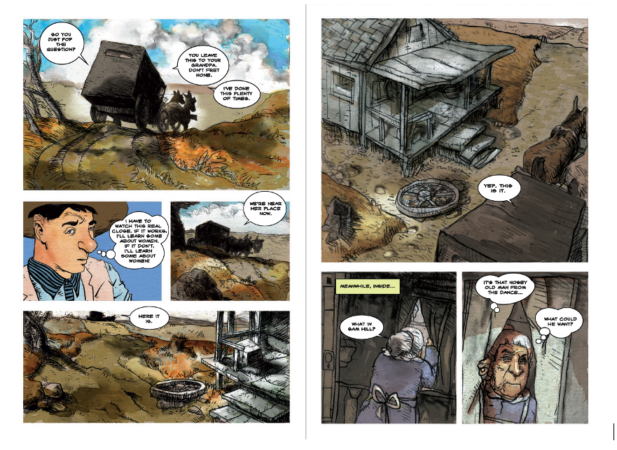

David Greg Taylor: Once again, thank you. Around 2012, I got back into etching. One of my degrees is in printmaking, but its toxicity caused me to pause after grad school. Then I discovered nontoxic intaglio printmaking and went back to doing etchings. With my typical hubris, I launched a series I named Le Suite Gesu as an answer to Picasso’s Vollard Suite. As an homage, but with my own take. I was telling stories with it, but it takes so long to do an etching, and then I developed a method of drawing that looks like what I was doing in etching. So, one day in 2018, I was doodling, and I drew the first drawing of Blueboy Brown. I decided to blend the two, comics and etching. I really learned how to do this by a concentrated study of Rembrandt’s prints. I draw as if it was an etching, with different layers of different depths that translate to dark and light marks. Rembrandt’s work has a characteristic manner of development that taught me a lot.

But to get back to the comics thing, when I returned to comics in 2018, I had all these stories in me and decided to incorporate what I learned from Ibsen and Shakespeare into my own cycle. Do theatre. It’s not Ibsen or Shakespeare (my hubris only goes so far), but a blend of all these ideas I’ve had pop into my mind, told in two families. You’ll only fully understand what I have to say by following both series. This isn’t me, like you wrote, taking up a long-running series. I teach art and cinema history college classes, and one of its foundations is Aristotle’s Theory of Happiness. I teach him principally because of two major errors in art in the last 100 or so years: D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, and the Futurists. Both art efforts led to dead people. BOAN restarted the KKK. The Futurists morphed into Italian political fascism allied with the Nazis. Art is not a neutral activity. It says “This is the way the world is. Do this.” Aristotle says happiness is what we all seek (do you want to be unhappy?) and it consists of certain things that are achievable, but only by living and making mistakes and correcting them. He says it takes a lifetime. Not everyone gets it. I agree with him, but along the way we must do no harm. That’s a tall order.

But to get back to the comics thing, when I returned to comics in 2018, I had all these stories in me and decided to incorporate what I learned from Ibsen and Shakespeare into my own cycle. Do theatre. It’s not Ibsen or Shakespeare (my hubris only goes so far), but a blend of all these ideas I’ve had pop into my mind, told in two families. You’ll only fully understand what I have to say by following both series. This isn’t me, like you wrote, taking up a long-running series. I teach art and cinema history college classes, and one of its foundations is Aristotle’s Theory of Happiness. I teach him principally because of two major errors in art in the last 100 or so years: D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, and the Futurists. Both art efforts led to dead people. BOAN restarted the KKK. The Futurists morphed into Italian political fascism allied with the Nazis. Art is not a neutral activity. It says “This is the way the world is. Do this.” Aristotle says happiness is what we all seek (do you want to be unhappy?) and it consists of certain things that are achievable, but only by living and making mistakes and correcting them. He says it takes a lifetime. Not everyone gets it. I agree with him, but along the way we must do no harm. That’s a tall order.

Griffith and the Futurists lost control of their message. Griffith said he was doing an anti-war film. He was not. The Futurists were naïve and nihilistic in thinking war and violence were cleansing agents. They were fools whose work is still lauded. Unbelievable. Art should aid us in seeking the good and realizing what that is. Art that spurs us to harm others is not, in my opinion, art. When I was in grad school, I took a seminar class whose second semester was being critiqued by major critics like Clement Greenberg and Donald Kuspit. The professor told me she didn’t pick me for the second semester because my work was about The Good. She said, “No one is interested in that.” It was the greatest compliment I’ve ever received as an artist, for my experience tells me that The Good is all anyone is interested in. I am trying, in my small way, to point in that direction. My investigation of theatre, thanks to Fjelde, taught me that great theatre does this. Tragedy tells us what happens when we don’t live well, and comedy, the happy ending, tells us what happens when we do, but I’ve found it is always by the skin of our teeth. We barely achieve it and it is precarious. The Good is not easy. The thing this professor thought we were interested in is loosy-goosy. It can be anything. I find that intellectually lazy.

Describe your art style and process.

I began drawing at the age of six. I’d been exposed to Alex Toth in the Dell Zorro comics the year before, which was 1958. I’ve been doing this for 64 years. I have so many ways of approaching art, I seem to adapt as the story demands it. I begin with a contour line drawing and add hatching and cross-hatching to that, sometimes on the page and sometimes in the computer. It’s a classical manner that I picked up from studying some Raphael drawings. It also is how I start etchings, so it seems to work. I have some sped-up drawings on YouTube that illustrates one manner I use. Wizards Leaping.

When doing these comics, I start out in a small sketchbook and map out the story in storyboards. Some of them make it into the comic if they look like they fit. This one made it in. What goes on here is I just draw. I’ve been doing it so long I just start on one small thing and then keep adding until it works.

They just seem to happen. I have an idea and I do it. Drives my Everyman buddies batty.

Joeseph Simon: Given your talk about the Futurists, Griffith, and so on, what do you think is the role of art in society? How can art be used to promote good and prevent harm?

David Greg Taylor: Art should first do no harm. If you look at the Futurists and Griffith, I would hope they weren’t aiming to harm (Griffith said BOAN was an antiwar film and look what we got!). The Futurists thought of war as a cleansing agent. Idiots. I’m very careful in what I depict. I have lived within an international culture and married into one (Cuban and Middle Eastern) since the late 80s, when I moved to New York, and I’ve taught and mentored students new to this country for over 30 years. In these latest stories I pick on organized crime. I don’t think any crime boss would read my stuff and think he was being unfairly focused upon. Anyway, the most evil people around probably blend in with society and look like regular folks. My crime boss does that. Everyone thinks he’s just rich. If they think any different, they’re dead.

In other words, don’t pick on the powerless.

Joeseph Simon: Both Afternoon comics have their roots in the past. Yet, Blueboy Brown will take place throughout generations of the Brown family. Liquid Prisoner throws us in the future. What about the past fascinates you?

David Greg Taylor: I think it has to do with my teaching art and cinema history. I love history. Also, I grew up with a father who could talk a squirrel out of a tree, and he wove tales that created images in me that harked to the past, especially in Blueboy Brown Comics. Some of the things in that comic happened to my great-great grandfather, who fought in the Civil War at age 14. Wonderful old guy. I have a photo of him as an old man. White beard to his waist. My dad knew him. He told some wild tales about him. Some of them he made up, but they were wonderful to listen to. So, I have a connection to these events. I “know” my characters and they speak to me. I think other writers have said the same thing. My take is “how did we get here?” I say in the inside back cover of one issue that these stories are the chronicle of a family of no real importance. I’m fascinated by the unimportance of ordinary people.

Joeseph Simon: To many people you are a new talent, the reality is something different. Your start in comics actually goes back to the 70s. Talk about that.

David Greg Taylor: I met a fanzine publisher in my first year of college at Missouri State University, in 1971. He published my first comics story Elyth, in 1972, in Realm #5. I was 19. I went to Colorado the next year for a while and drew Hobo Stories, which was what Dale Luciano wrote about in The Comics Journal in ’85. (I was for a short time a part of Everyman Studios in Colorado Springs). HB was an underground comic and right as I finished it, undergrounds went into the ditch. But I did get to watch Gilbert Shelton draw a Furry Freak Brothers episode when he was looking at and rejecting my book. Really nice person, and I remembered everything he did that day while drawing that strip. My book finally got published in 1979, too late for undergrounds and too early for indies. I was quite cold on it by that time. I’d moved on to printmaking, etchings. I couldn’t see any future for me in comics, and I needed seasoning. I needed life experience. I started taking care of invalids to finance college. A new friend introduced himself to me at a party back then and said, “Are you the Dave Taylor from The Comics Journal?” He showed the issue to me. This was the first I’d heard about it. After MSU, I moved to Brooklyn for grad school at Pratt, and started teaching in Florida a few years later. Got married. Got a mortgage. Regular life until I retired and got back into comics.

Joeseph Simon: Talk about Everyman. Who else was in Everyman and are they still around?

David Greg Taylor: Everyman Studios was the official name. It consisted of Rick Berry, Darrel Anderson, the late Kirk Kennedy, and Artie Romero. Everyone but Kirk is still around doing art. Rick is a very well-known sci-fi/fantasy illustrator. Darrel created the coolest 3D app I ever used, Groboto (and is a top-notch sci-fi illustrator too along with the math genius stuff). Kirk passed away about thirteen years ago but was the funkiest cartoonist. Artie Romero is our Walt Disney, doing animation to this day, winning awards at international film festivals.

I lost contact with all of them until the web started in the mid-90s and have stayed in touch since then. Another Everyman, Allan Greenier is part of the present scene and just published a postcard set of Everyman sci-fi and some of my Blueboy Brown sketchbook stuff. Allan is a woodcut printmaker. Does really huge woodcuts. Blows my mind.

Joeseph Simon: What creators back then inspired you and what ones would you say do now?

David Greg Taylor: Alex Toth still inspires me. Everyone I liked back then (the 60s) was following him. Everyone that informs my drawing now are the big guns in art: Rembrandt, Raphael, Michelangelo, Ingres, Picasso, Matisse, Mary Cassatt. People who could draw. Also, Jean Giraud/Moebius. I ran across the first French editions of Lt. Blueberry back in 1972 and they rattled my cage. Still do.

In writing, my first love was Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. A very old children’s book from the 1950s had a big effect on me, Crow Boy. Read it when I was maybe eight. I found a copy of it some years back and now treasure it. I love Raymond Carver, Eudora Welty, Flannery O’Connor, Walker Percy, Graham Greene, W.B.Yeats, Richard Stark/Donald Westlake’s Parker novels, Shakespeare forever(!). One of my boyhood favorites was Robert Heinlein. Also Phillip K. Dick. Still like Ibsen. The philosopher Edith Stein has had a huge effect on me and my worldview. Her PhD dissertation On the Problem of Empathy hit me like a ton of bricks. She is maybe the smartest person I’ve read from the last century (another reason to loathe the Nazis, who killed her). I own everything she wrote.

Joeseph Simon: Is it fair to say you straddle the realms of avant-garde, underground, and literary comics and merge them with pulp?

Joeseph Simon: Is it fair to say you straddle the realms of avant-garde, underground, and literary comics and merge them with pulp?

David Greg Taylor: I am still an underground cartoonist, but at my age the underground is, for me, completely different than when I was 20. I know what works and what doesn’t work. I rubbed shoulders with some unsavory characters in my youth. I’m amazed I survived. The writing thing is what lights my fire these days. Because I have seen true evil and true good, I believe I can navigate within the pendulum between the two in writing. I love doing comics, because it incorporates every experience I’ve had as an artist since I was first published 51 years ago. I’ve done underground comics and lectured on Velasquez at the Met. Now I’m unwinding all that into my comics.

Joeseph Simon: A lot of the industry has changed since the days of Everyman. What about those changes excite you and what scares you?

David Greg Taylor: First and foremost, you can do an end-around for the corporate publishers and do it through crowdfunding. If that had existed back in the 70s, I’d have done it then, despite the results. Being able to ignore the suits and committees that dictate stories and content is a big deal for me. I’m a recluse and could never have done that. I also don’t usually have the capacity to work for other people. I’m in my own world. (Though I did do a commissioned superhero story for Victor Dandridge’s Vantage: In-House comics last summer. Very cool story, so I did one superhero thing in my life).

What scares me? Nothing really. I could talk about what I like and don’t like, but let history do that for me. The cream will rise to the top. That may not be me, but I gave it the old college try.

Joeseph Simon: From Everyman, time passed, and Afternoon Comics was born. Tell us the who, what, where, and why’s?

David Greg Taylor: Like I said, in August 2018 I did this drawing that started me back on comics. I sent it to Rick Berry, and he liked it. I nagged him with every new drawing in the comic for the next few years, and he put up with me. That’s what friends do. I’m trying to control my tendency to shoot off ten emails a day.

I adapted a short story I’d written around 2008 and it peopled the Blueboy Brown Comics series. I’ve done five of those; working on the sixth one now and then at the beginning of 2023 I started working on Liquid Prisoner Comics #1. My first comic, Elyth, was a scifi story, and I’ve always been a big SF fan. I watched 2001: A Space Odyssey three times the first day I saw it. I began in the afternoon and stayed in the theatre until it closed. This was in 1970. I saw it maybe thirty times in the next decade. No VHS, DVDs or anything like that back then.

Around 2014 or so, I read Uncommon Talent by Jason Brubaker and it was the first time I’d even been aware of crowdfunding. In 2019, I spent about a year and a half streaming the creation of the first version of Blueboy Brown as a webcomic on YouTube and Facebook, and then rewrote the whole thing as a hard copy and launched it on Kickstarter in late 2020, during the pandemic. I got funded in about four hours. Out of that came a small fan club called The Tree Punks that feeds a newsletter.

Joeseph Simon: What’s next for Everyman?

David Greg Taylor: Well, we’re all old-timers, so we just do art and send it to each other via email. I’m on Facebook and you can subscribe to the Tree Punks newsletter at afternooncomics.com/newsletter if anyone wants to keep up with what I’m doing. I’m starting an Etsy store to hawk prints and tee shirts. I plan a hardcover of Blueboy Brown Comics soon. It might coincide with the Blueboy Brown Comics #6 Kickstarter, which begins the Black & White issues. That’s slated for early 2024. Things are about to get very noir for Blueboy. I have the next issue of Liquid Prisoner Comics mapped out. We go off-world and meet the Liquid Prisoner itself.

Joeseph Simon: Tell me about your upcoming project? What when and where can readers get it?

I am finishing up Blueboy Brown Comics #6. It should be launching on Kickstarter in late February or early March.

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/blueboybrowncomics/blueboy-brown-comics-6

After that is done, I begin work on Liquid Prisoner Comics #2. My scifi comic.

I’m really enjoying this part of my life.